EPR 101 by Representative Sydney Jordan

Understand Circular Policy fundamentals, definitions, and answers to common questions about producer accountability.

Goals of the Guide

This guide is a neutral resource for state legislators in the U.S. considering Extended Producer Responsibility. It explains what Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for packaging is, takeaways from legislators and staff who passed EPR in their states, and input from advocacy organizations and stakeholders across the value chain. This guide does not advocate for EPR or any particular policy; in fact, you will see conflicting recommendations from different sources. We want to ensure that legislators have an easy framework for understanding what EPR for packing means, understand the major stakeholder groups they will engage with during policy development, provide and reflect on policy examples from across the United States, and establish shared language informed by experts.

Ultimately, we hope legislators can use this as a guide- you have limited time and staff resources and need information to be clear and precise. Use this to learn more about what EPR does, how it is currently being implemented across the U.S., find what has worked for past legislators in your shoes, prepare for your next meeting by hearing what that stakeholder has to say, and ultimately decide what, if any, policies you want to pursue for your state.

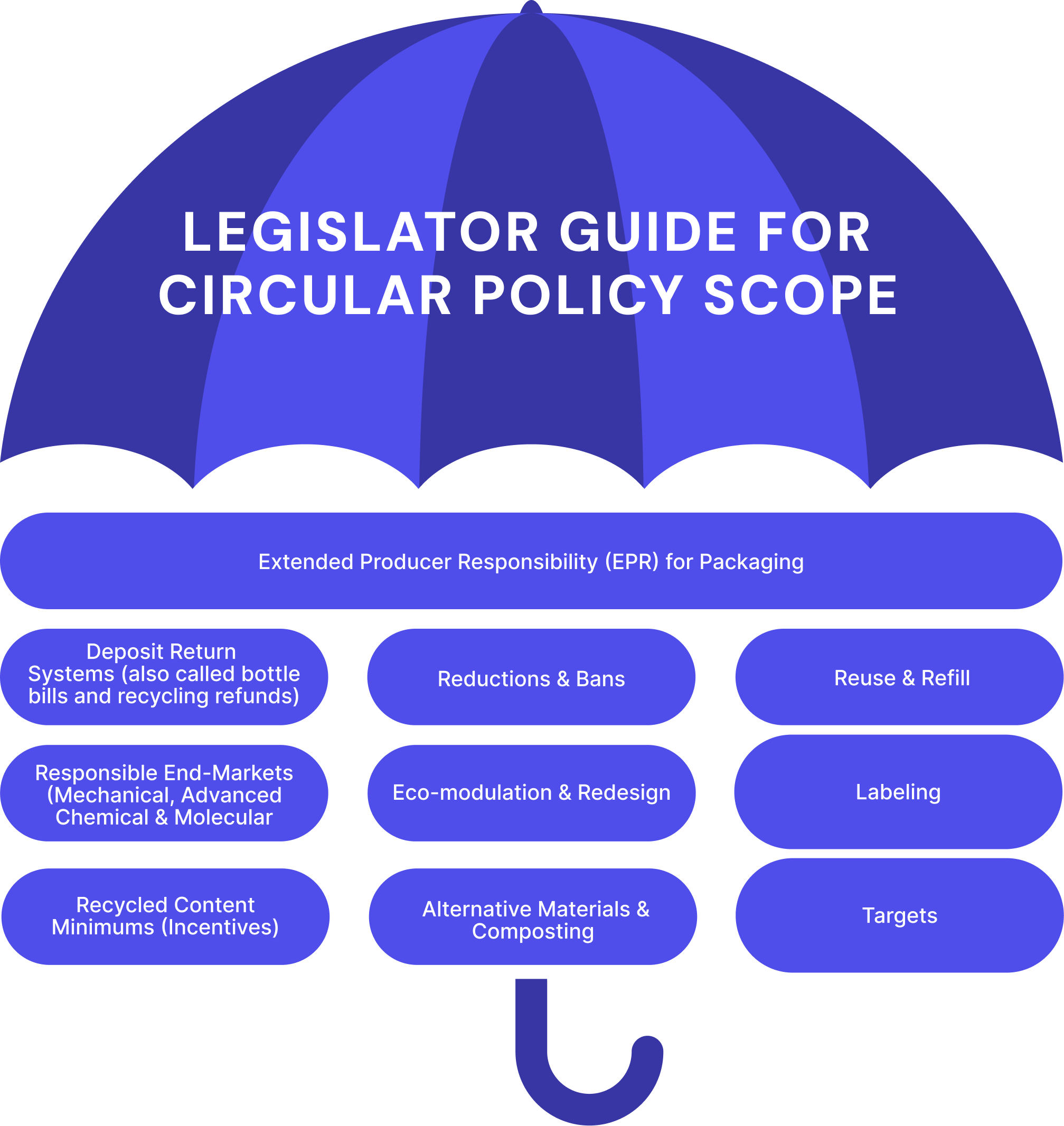

Umbrella Graphic - Understanding Key Technical Topics

Legislators will encounter a range of technical themes when considering EPR for packaging. Stakeholders bring different perspectives on how to incorporate these elements, and different state policies take different approaches. The goal of this guide is to educate legislators on why these technical topics relate to EPR for packaging systems through the multi-stakeholder lens.

EPR and Circular Policy Framework

EPR stands for “Extended Producer Responsibility,” and could be used to describe any product stewardship program where producers, generally the brand owner of a product, take responsibility for the disposal or recycling of a product they make. It is an umbrella term for many policies that can increase circularity and include producers of waste in the recovery and recycling through fees and financial incentives.

In this guide, we are specifically discussing EPR for packaging and printed materials. EPR is a paradigm shift where the producers of packaging waste are responsible for the end-of-life of the packaging their products come in. This is an evolution of existing solid waste systems, where consumers and governments are responsible for that packaging through taxes, municipal budgets and other supports, either by paying for it to be recycled or placed in a landfill or incinerator.

U.S. EPR for packaging

As of January 2026, 7 states have passed EPR for packaging legislation. These are:

- Maine 2021: LD 1541: An Act To Support and Improve Municipal Recycling Programs and Save Taxpayer Money

- Oregon 2021: SB 582: Plastic Pollution and Recycling Modernization Act

- Colorado 2022: HB22-1355: Producer Responsibility Program for Statewide Recycling Act

- California 2022: SB 54: Plastic Pollution Prevention and Packaging Producer Responsibility Act

- Minnesota 2024: HF3577: Packaging Waste and Cost Reduction Act

- Maryland 2025: SB 901: Packaging and Paper Products – Producer Responsibility Plans Act

- Washington 2025: SB 5284: Recycling Reform Act

Stakeholder Roles and Responsibilities

Across much of the US, either a local government or a property owner is responsible for managing a contract with a waste hauler who picks up the recycling and takes it to a Material Recovery Facility (MRF). MRFs are where recycled materials are sorted to be sent to end markets where they are transformed into new products. Systems are constrained by the resources a government or individual has to invest in the recycling process.

Under an EPR system, the responsibility for recovery and recycling shifts from municipalities and property owners to producers. Rather than require individual producers to recycle their packaging, EPR programs require the formation of a joint compliance organization, known as a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO). The PRO represents the producers and runs the EPR program on their behalf.

The Advisory Council (sometimes called Advisory Board) is a group of stakeholders representing populations and organizations impacted by a state’s EPR law. They oversee and provide feedback to both the PRO and the state governmental agency managing recycling. The regulating state agency (often the state’s equivalent of the federal EPA) oversees the program, makes sure the Advisory Council meets and fulfills its role, and provides oversight of the PRO.

The relationships, roles, and financial flows between these bodies and governments vary across states - you will read different stakeholder recommendations for these structures.

Differences and Similarities in State EPR

A goal of EPR is to achieve circularity or a circular economy, where packaging waste is diverted from landfills or incinerators through shifting to a system where packaging is reused or recycled into another product, where it can go back on the market for future use.

EPR systems look different across states, even when policymakers attempt to harmonize with existing EPR systems- your state has a unique culture, economy, and local stakeholders that will shape the bills you consider and decide to work on. Not every legislature will decide to incorporate every element under the EPR “umbrella,” but we want you to have an understanding of what they are and how the policy works in a circular economy.

As more EPR legislation is passed, policymakers are looking to other states for reference. A high-level overview of state comparisons is summarized in this table from The Recycling Partnership.

Special thanks to The Recycling Partnership, Upstream, and the Biodegradable Products Institute for their technical support to 101 and Key Terms sections.

Key Terms

EPR contains many confusing and technical terms lawmakers do not typically encounter when writing bills. Use this section to look up what a stakeholder might be referring to or to better understand the components of what could be included in a definition of EPR. In this section, we explain the term using previous reports and work done from our technical partners, The Recycling Partnership, The Biodegradable Products Institute, and Upstream. After the definition, we also include any needed context for how this word or phrase comes up when discussing EPR.

The circular economy is a system where materials never become waste and nature is regenerated. In a circular economy, products and materials are kept in circulation through processes like maintenance, reuse, refurbishment, remanufacture, recycling, and composting. The circular economy tackles climate change and other global challenges, like biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution, by decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources.

EPR stands for “Extended Producer Responsibility,” and could be used to describe any product stewardship program where producers take responsibility for the product’s end of life, i.e.- recycling or reuse.

In this guide, we specifically refer to EPR for packaging and paper, which is defined as “a policy approach that requires producers (i.e., brands) of packaging and printed paper to finance the costs of recycling — from education to collection and sorting, as well as other related activities — with the goal of increasing recycling rates.” Seven states have EPR laws and are in various stages of implementing the laws.

Also called “Deposit Return Systems (DRS),” “recycling refunds,” “bottle bills,” or “EPR for beverage containers,” this is a policy approach that requires producers of beverage packaging to fund and operate a specialized, separate recycling infrastructure. Ten states have a legislatively mandated Recycling Refund system; California, Maine, and Oregon have both Recycling Refunds and EPR. Recycling Refunds, or DRS, provide an economic incentive to consumers to return used beverage packaging to be recycled, and incentivize producers to use recyclable packaging materials and designs. Consumers pay a small deposit when purchasing a beverage and are then refunded the deposit when the beverage package is returned.

Some stakeholders want to see recycling refund included as a part of U.S. EPR legislation, while others view it as separate.

These are phrases that are often used when discussing EPR, which both mean technological processes of recycling plastic material by changing the molecular structure. There are different types of chemical recycling such as pyrolysis, gasification, depolymerization, and other processes. Depending on the process, it creates new plastics, fuels, and/or other chemicals.

You will be asked to consider the role of chemical recycling in your state’s EPR policy. It is up to each state to determine if this form of recycling fits within your state’s statutory definition of recycling and if and how to include it within EPR targets.

Many proponents of EPR disagree about its role. Advocates for the inclusion of chemical recycling in EPR systems point out the difficulty in recycling some common plastic packaging materials through a mechanical recycling system and the ability of chemical recycling to produce food-grade materials to the FDA standard. Opponents of chemical recycling cite concerns about its reliance on fossil fuels and its production and transportation effects on human health and the environment, particularly in environmental justice communities.

The Advisory Council (sometimes called Advisory Board) is a group of stakeholders representing populations and organizations impacted by a state’s EPR law. They oversee and provide feedback to both the PRO and the state governmental agency managing recycling.

Most states that have passed an EPR law have included an Advisory Council in the legislation. It is dependent on each state to decide which groups they want to serve on the Advisory Council, but is typically made up of representatives from other units of government, waste haulers, recycling experts, and/or advocates for various causes related to solid waste.

is the product manufactured through the controlled aerobic, biological decomposition of biodegradable materials (BPI).

Compost is something you will need to consider in the context of labelling and packaging redesigns. You will need to consider if/how EPR will fund organic recycling infrastructure (i.e. composting infrastructure) and the existing composting infrastructure. Many states are contemplating how best to incorporate composting as part of their solid waste system and you should consider how you want to approach it as a part of EPR.

In public policy, Environmental Justice refers to the fair and meaningful involvement of all affected parties regardless of race, class, gender, background or socioeconomic status in determining environmental policy. (EPA) In recycling practice, this means all people have equitable access to recycling, reuse, and/or compost systems and that changes to recycling policy lessens the varying health and environmental outcomes across communities.

Legislators should familiarize themselves with this concept because it is often used when discussing EPR. Many community members will cite the need for Environmental Justice as a reason to push EPR and other policies. Several states have included advocates for Environmental Justice as Advisory Board members. You will also hear critiques of aspects of EPR because it may or may not address Environmental Justice concerns. Environmental Justice is often included in discussions about siting recovery and recycling infrastructure funded by EPR.

Harmonization is when lawmakers align definitions and statutes to other states for ease of doing business across state lines.

Many advocates for EPR will approach you about harmonizing your law with existing EPR laws. This could range from simple harmonizing acts like aligning statutory definitions to asking to copy existing laws from other states. In existing states, lawmakers were approached about harmonizing definitions of producers, end markets, and fee setting structures.

Labels of products containing clear, accurate, standardized recyclability or composting claims. Labeling requirements ensure consumers are educated on how to recycle an item and safeguard against contamination in recycling streams.

Certain stakeholders will note that labeling requirements are not uniform for all products across geographies, confusing consumers. Others will state that labeling needs to consider local recycling infrastructure. You will read different recommendations for how to address labeling and design standards.

Mechanical Recycling is the process of recycling products without changing the molecular structure. This usually involved sorting, washing, shredding, and/or melting.

It is commonly used when talking about plastic recycling, especially when discussing the role of Advanced Chemical/Molecular Recycling in EPR legislation.

Mechanical Recycling is the form of recycling you are likely most familiar with. Machines in your Material Recovery Facilities (MRF) typically do sorting and baling before materials are sent to converters and manufacturers, who shape the material into a new product.

A needs assessment is a detailed analysis of a state’s current recycling system that identifies what a state requires to meet the goals of an EPR law — including but not limited to the infrastructure, services, education, and funding needed to improve collection, sorting, processing, and recycling. It outlines current gaps, calculates the full costs to close them, and provides a roadmap for achieving the program’s targets.

In an EPR law, the Needs Assessment is different from the actual PRO plan- think of this as the “why” and the PRO plan as the “how.” A Needs Assessment is heavily influenced by the language of the law, and the entities working to fulfill the law, the state agency, the PRO, and the Advisory Council. You will hear varying perspectives about the sequencing, content, and stakeholder responsibilities in a Needs Assessment.

The physical material used to contain, protect, and present a consumer product up to the point of sale. This includes all components: primary container, caps, labels, films, and shrink wraps. Printed Paper is paper-based materials that carry some form of print, for example: newspapers, mail, catalogs, and office paper. These are the materials that you would sort into the paper portion of your recycling.

Most U.S. EPR legislation covers packaging and paper. Some also include plastic foodware (e.g. plastic utensils or containers). States differ in their approaches to whether business to business packaging and paper are included. An overview is included in this table from The Recycling Partnership.

Changing a product’s packaging to make it more recyclable.

This will be a key discussion point. If you are interested in policies that promote recycling, many products have packaging that will need to be designed for ease of recycling and bills you introduce will need to have mechanisms for promoting redesign (see Eco-modulated fees). Stakeholders may also call for investment in recycling infrastructure as packaging is redesigned.

Material that was used, recycled, and processed into a new material on the market.

PCR content differs from “virgin” products that have no previously used and recycled material in them. Many EPR policies contain PCR minimums as a target for brands to achieve in their packaging.

Generally, EPR laws aim to make the brand owner of the paper and packaging waste the obligated producer.

The nuances of this definition are defined by each state in its statute. Many states have started harmonizing the definition of producer. Policy makers should also consider definitions for de minimis producers, or producers who introduce very little packaging waste into the waste stream or are small businesses.

To finance the recycling system for packaging, producers (e.g., brands) of packaging and printed paper create and manage a central producer responsibility organization (PRO) to administer the funds and support reaching the recycling goals laid out in statute. (TRP)

Essentially, this refers to a group of brands and producers that contribute fees to the EPR system as a result of making products with packaging and paper. They are an entity that collects the fees and manages the EPR system to reduce the administrative burden for individual producers.

The PRO has different roles in different states. Stakeholders bring recommendations for PRO roles, such as involving the PRO in needs assessments or the role of the PRO in managing recycling service contracts. One of the key deliverables from the PRO is the “PRO Plan”, the PRO’s detailed strategy to meet the financial and operational goals in the legislation.

Producer fees that vary based on the amount and type of packaging a producer introduces into a state’s system. In an EPR system, producers pay fees that reflect the true sorting, recycling, and end-of-life costs of each item. Fees can be lower or higher depending on the packaging’s ability to be reused, recycled, or composted within a state’s infrastructure. Some states have fees set so producers pay for the entirety of the cost of recycling packaging. Other states require that producers pay only a portion of the recycling costs. Fees are set by the PRO.

Eco-modulation refers to adjustments of an individual producer’s fees that depend on environmental attributes of packaging. For example, design factors that make packaging more recyclable would decrease a producer’s fees, while design factors that make packaging less recyclable would increase a producer’s fees (e.g., use of inks, labels, adhesives, etc., that can render a package less recyclable).

Packaging designed to be refilled by consumers multiple times for the same or similar purpose in its original format, and is sold or provided to consumers once for the duration of its usable life. (Upstream). This is a type of “reusable” packaging.

Some U.S. EPR policies include reuse and reduction targets in addition to recycling targets. You will hear varying perspectives on the role of reuse in EPR legislation; e.g., certain stakeholders will note that reuse systems require different infrastructure, while others state that recycling infrastructure alone cannot handle growing material volumes.

Packaging designed to be recirculated multiple times for the same or similar purpose in its original format in a system for reuse, and is owned by producers or a third party and returned to producers or a third party after each use. (Upstream)

See above for more points on reuse. Returnable Reusable packaging is gaining momentum as it has unique needs in a reuse system.

A materials market in which the recycling or recovery of materials or the disposal of contaminants is conducted in a way that benefits the environment and minimizes risks to public health and worker health and safety. (TRP)

End Markets are essentially where the materials end up in a recycling system. You will hear Responsible End Markets when discussing the definition of recycling in your legislation. Policy makers should consider what options exist locally, regionally, nationally, and maybe internationally, and how your recycling program ensures materials end up where you want.

Specific and measurable goals for a state’s EPR program. The producers are held accountable by state agencies for reaching these goals and EPR programs provide incentives to achieve these goals.

If you are pursuing an EPR policy for your state, you will have to contemplate how to set targets and what they should be. You should consider how established your existing recycling system is, whether or not you want targets set by the legislature, the PRO, or the regulating state agency (often the state’s equivalent of the federal EPA) and what targets should be.

A value chain is every person, business, process, and retailer that takes an item from its raw materials to a sold product to its eventual disposal or reclamation through recycling, composting, or reuse. This includes the product and its packaging, but it also includes the actual people and businesses, including material sourcing, production, consumption, recycling, or disposal in a landfill or incinerator.

This phrase is used rarely in government and constantly in the private sector. Understanding the packaging value chain helps you, as a legislator, identify where improvements can be made in the system and which entity controls a product. This matters as the control is constantly changing as an item and its packaging move through the system. There are many people and processes that go into getting a product and its packaging from raw materials to a final good purchased by a consumer and many people and processes that handle the end of life of a product's packaging through the disposal and reclamation.